[Food's Profile] The Case of English Muffins

From Edwardian teatables to literary plots: a story soaked in tradition — and butter

Welcome to Read and Eat, a free newslatter uncovering what food does in fiction — how it builds worlds, reveals characters, and makes us part of the story.

If you enjoy this literary deep-dive, consider subscribing so you won’t miss the next course.

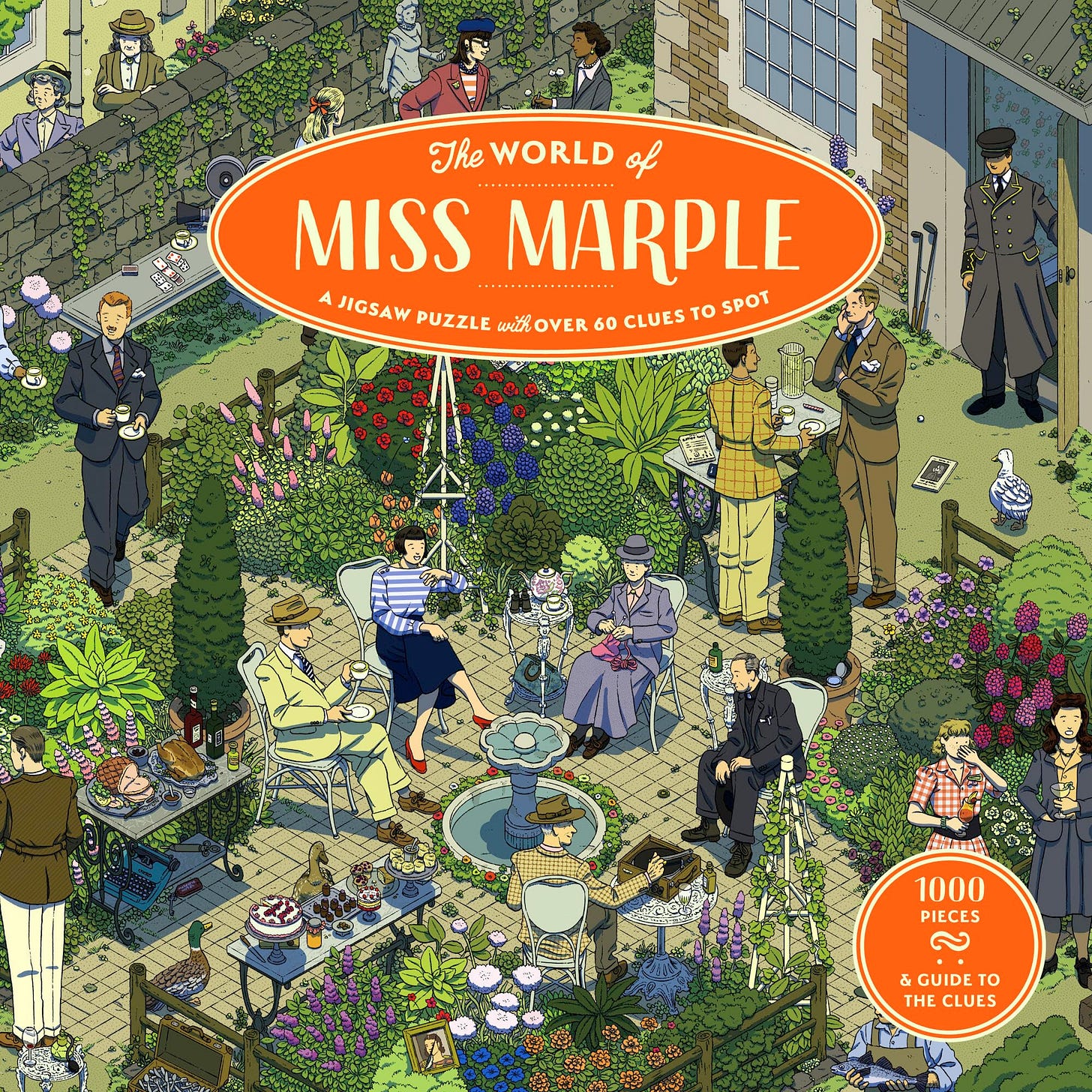

Here’s a mystery worthy of Miss Marple: what’s wrong with this picture?

What you see is a jigsaw puzzle illustrated by Ilya Milstein. It is filled with all kinds of references to Agatha Christie’s mysteries featuring her most famous female sleuth. I smile contentedly, studying the edible clues — but not for long. Then I notice something among the tea treats that makes me laugh and wince at the same time.

For those unable to spot all the hidden references, the puzzle comes with a detailed key. And it confirms my suspicion: under the label ‘muffins’ from At Bertram’s Hotel (English muffins, that is), we see foreign impostors — something that clearly looks like American-style blueberry muffins. This detail is especially ironic, given that in the novel Lady Selina complains about the very same mix-up.

Is this an intentional joke? Maybe — but I wouldn’t bet on it.

This jigsaw puzzle is part of the official merchandise produced by Agatha Christie Limited. If the experts on the author’s legacy allow for such ambiguity, what can we expect from ordinary mortals? English muffins are a source of eternal confusion. But let’s start at the beginning.

The Best of the Best

Let’s talk national treasures. How does one determine them — culinary-wise? How can you tell which dish truly counts as a national icon?

Try as you might, the answer isn’t obvious — not even to someone within the culture. Or maybe it’s just me: I’ve always found it difficult to choose just one, the single most emblematic dish that could represent my home country on the global gastronomic stage.

For the British, it might be even trickier. For centuries, the reputation of English food has been dubious — not only among foreigners, but even among the more ‘refined’ locals themselves. ‘The best English cooking is French’ isn’t exactly a joke. Even if it isn’t true either.

In 1945, George Orwell wrote his famous essay In Defence of English Cooking. There’s plenty to enjoy in it, but one particular idea caught my attention.

To identify the true gems of English cuisine, Orwell suggests a simple test: What would an Englishman miss most when living abroad? And he doesn’t hesitate to give his answer:

First of all, kippers, Yorkshire pudding, Devonshire cream, muffins and crumpets.

A peculiar bunch from today’s perspective, isn’t it? Orwell does go on to name many other things — but these are his immediate culinary associations.

The entire essay is a fascinating snapshot of mid-20th-century England — a kind of conservation area where all the treasures are kept untouched, while the ‘outer world’ has changed dramatically. World War II and the post-war years of rationing reshaped the national diet: some dishes quietly faded away, others shifted in meaning or status.

Take, for example, the tradition of afternoon tea.

Today, the default baked companion to tea is the scone. It’s everywhere — from humble family-run tearooms to five-star hotels. But English muffins? You’ll mostly find them sealed in plastic on supermarket shelves, meant to be toasted at home. Or maybe in a handful of specialty tearooms — if you know where to look. (Please share your local knowledge in the comments if you do.)

And yet, during a certain period, muffins were a familiar sight at the tea tables of respectable society. I’d go so far as to say that muffins were the ‘Edwardian scones’ of the well-to-do. At least, this is how it looks from a fiction reader’s perspective.

Let’s Talk Terminology

First of all, don’t confuse English muffins with American ones (and don’t confuse American muffins with cupcakes — though that’s a subject for another investigation). When we say ‘muffin’ today, we often picture a sweet, cake-like pastry in a paper case. But an English muffin is something entirely different.

Essentially, it’s a type of yeasted white bread — the only quirk being the method of cooking. English muffins are baked on a griddle or flat pan, not in the oven — just like many other traditional British breads, such as crumpets, bannocks, or Scottish oatcakes.

Fireplace Baking

A whole range of traditional British cooking practices stems from one simple fact: for a long time, most households didn’t have proper baking facilities — anything resembling a modern oven. The only available heat source was the open fire. And that’s what people used to make simple breads. Alternatively, in urban settings, you’d buy bread at the bakery — and still toast it at home, over the same fire.

To bake bread (or rather, buns) at home, a special tool was used: a heavy iron disc with a handle, called griddle — or girdle in Scots. These days, a sturdy cast-iron skillet does the job just as well.

This method of stovetop baking gave rise to all sorts of regional variations across the country. But English muffins stand apart.

To paint in broad strokes: crumpets are essentially yeasted pancakes, Scottish potato scones are more like flatbreads, and Welsh cakes resemble sweet scones in every way except for thickness and the way they’re cooked. Meanwhile, English muffins are bread — in the most classic sense of the word.

They’re shaped into individual rounds out of necessity — otherwise, they wouldn’t cook through. But what they’re made of is unmistakably bread dough: yeasted, soft, slightly enriched. Everything about the process follows standard bread-making — until the very last step.

Establishing the Rules

If you took the same dough, rolled it into balls, and baked them in the oven, you’d get charming little dinner rolls, each a perfect dome. On a griddle, however, muffins follow the rules of pancakes: they turn flat as they’re flipped from side to side. Their tops and bottoms become golden brown; their sides remain pale and soft to the touch. Inside, the crumb is fluffy and tender, eager to soak up every bit of melted butter it receives — always a sign of excellence in British teatime breads.

In fact, eating English muffins without butter is unthinkable — at least historically. And for the butter to melt properly, the muffins must be hot — straight off the griddle. If they’ve cooled down (or come pre-packaged from a shop), serving them as-is simply won’t do. That said, they go cold quickly — which is why old recipes often include a final step: reheating and buttering right before serving.

These days, the easiest way to do that is to split the muffin and pop it into the toaster. A universal solution — but not historically accurate. So how would the experts of the past go about it?

First: a freshly baked English muffin should never be cut with a knife — only torn open by hand. This rule appears as early as 1747 in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse — one of the first printed sources to mention English muffins. Glasse insists that cutting them with a knife makes the crumb ‘as heavy as lead.’ Muffins may only be cut after they’ve been toasted, buttered, and fully warmed through — and even then, only for ease of eating.

Also worth noting: the crumb is not meant to be toasted — just gently warmed, while remaining tender and airy. So if you’re using a modern toaster, avoid the standard mode. Go for the ‘bagel’ setting instead, and make sure the muffin halves are facing the right way.

Here’s the old-school serving method in full:

Tear the muffin gently around its edge, as if to separate it into top and bottom, but leave the center intact.

Spear it on a long toasting fork and hold over an open fire until one side browns nicely (but doesn’t burn).

Flip and toast the other side.

Take the muffin off the fork, split it completely, and insert a generous amount of butter between the halves — not spreading, just stuffing in chunks.

Close the muffin back up like a sandwich, and place it on a hot dish near the hearth to stay warm and soak up the butter.

Repeat as needed — and make sure the whole batch is still hot when served.

Nowadays, a real hearth at home is a rare luxury. So we improvise: oven, pan, toaster — go for it, Hannah Glasse won’t see. You might even try the barbecue grill.

For modern consumers, the English muffin is best known as the base of that iconic brunch dish, eggs Benedict — served with poached eggs, bacon, and hollandaise sauce. English literature, however, paints a very different picture. There, muffins belong to the afternoon — universally served as part of tea, in the simplest, most traditional form: toasted, stacked high, and dripping with butter.

Oscar Wilde Makes an Entrance

The first literary mention of muffins that truly struck a chord with me was in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). Food is used generously throughout the play to amplify its comic effect — think of the famous cucumber sandwiches, for instance.

Muffins may be less iconic in Wilde’s oeuvre, but on stage, they serve a similar purpose.

JACK.

How can you sit there, calmly eating muffins when we are in this horrible trouble, I can’t make out. You seem to me to be perfectly heartless.

ALGERNON.

Well, I can’t eat muffins in an agitated manner. The butter would probably get on my cuffs. One should always eat muffins quite calmly. It is the only way to eat them.

JACK.

I say it’s perfectly heartless your eating muffins at all, under the circumstances.

ALGERNON.

When I am in trouble, eating is the only thing that consoles me. Indeed, when I am in really great trouble, as any one who knows me intimately will tell you, I refuse everything except food and drink. At the present moment I am eating muffins because I am unhappy. Besides, I am particularly fond of muffins. [Rising.]

JACK.

[Rising.] Well, that is no reason why you should eat them all in that greedy way. [Takes muffins from Algernon.]

ALGERNON.

[Offering tea-cake.] I wish you would have tea-cake instead. I don’t like tea-cake.

JACK.

Good heavens! I suppose a man may eat his own muffins in his own garden.

ALGERNON.

But you have just said it was perfectly heartless to eat muffins.

JACK.

I said it was perfectly heartless of you, under the circumstances. That is a very different thing.

ALGERNON.

That may be. But the muffins are the same. [He seizes the muffin-dish from Jack.]

Wilde’s characters argue over whether eating muffins is compatible with emotional distress — and appear to agree that no amount of inner turmoil should ever interfere with a good muffin. No surprise there, from where I’m standing.

Bernard Shaw on the Banality of Muffins

The tension between emotion and the everyday reality of muffins wasn’t lost on George Bernard Shaw either. He frames it differently, contrasting the banality of muffins with the lofty idea of romantic inspiration. In Man and Superman (1903), muffins become a metaphor for something thoroughly mundane — unfit to spark the artist’s fire, even if not without their own primitive appeal.

OCTAVIUS.

I cannot write without inspiration. And nobody can give me that except Ann.

TANNER.

Well, hadn’t you better get it from her at a safe distance? Petrarch didn’t see half as much of Laura, nor Dante of Beatrice, as you see of Ann now; and yet they wrote first-rate poetry—at least so I’m told. They never exposed their idolatry to the test of domestic familiarity; and it lasted them to their graves. Marry Ann and at the end of a week you’ll find no more inspiration than in a plate of muffins.

OCTAVIUS.

You think I shall tire of her.

TANNER.

Not at all: you don’t get tired of muffins. But you don’t find inspiration in them; and you won’t in her when she ceases to be a poet’s dream and becomes a solid eleven stone wife. You’ll be forced to dream about somebody else; and then there will be a row.

Feeding the Revolutionaries with P. G. Wodehouse

Why do muffins come across as somewhat unrefined? Perhaps because they’re sturdy, filling food — not like those delicate cucumber sandwiches or paper-thin slices of buttered bread typical of aristocratic teas.

That’s right, we’ve just seen them appear at tea in a gentleman’s household — and yet they’re substantial enough to satisfy the working class. P. G. Wodehouse plays with this contrast in his 1923 short story ‘Comrade Bingo.’

“I tell you what, are you doing anything to-morrow afternoon?”

“Nothing special. Why?”

“Good! Then you can have us all to tea at your flat. I had promised to take the crowd to Lyons’ Popular Café after a meeting we’re holding down in Lambeth, but I can save money this way; and, believe me, laddie, nowadays, as far as I’m concerned, a penny saved is a penny earned. […] Well, thanks for your cordial invitation for to-morrow, old thing. We shall be delighted to accept. Do us well, laddie, and blessings shall reward you. By the way, I may have misled you by using the word ‘tea.’ None of your wafer slices of bread-and-butter. We’re good trenchermen, we of the Revolution. What we shall require will be something on the order of scrambled eggs, muffins, jam, ham, cake and sardines. Expect us at five sharp.”

Muffins for a gentleman’s tea? Acceptable. But scrambled eggs, ham, and sardines? That’s crossing a line. Bertie Wooster is hesitant to relay these demands to Jeeves — and wisely begins with the muffins, the least scandalous item on the list.

In another Wodehouse’s story, ‘Open House’ (1933), muffins again appear at tea. This time, the offerings are strictly genteel: cucumber sandwiches, sultana cake, and muffins. All of which the protagonist proceeds to hurl at a cat in a frantic attempt to save a canary:

And, springing quickly to the teatable, he rummaged among its contents for something that would serve him as ammunition in the fray.

The first thing he put his hand on was the plate of cucumber sandwiches. These, with all the rapidity at his command, he discharged, one after the other. But, though a few found their mark, there was nothing in the way of substantial results. The very nature of a cucumber sandwich makes it poor throwing. He could have obtained direct hits on Francis all day without slowing him up. In fact, the very moment after the last sandwich had struck him in the ribs, he was up in the air again, clawing hopefully.

William side-stepped once more, and Francis returned to earth. And Eustace, emotion ruining his aim, missed him by inches with a sultana cake, three muffins, and a lump of sugar. <…>

Eustace’s Aunt Georgiana was pointing dramatically.

“ He threw cucumber sandwiches at my cat ! ”

“ So I observe,” said Wotherspoon. He spoke in an unpleasant, quiet voice, and he was looking not unlike a high priest of one of the rougher religions who runs his eye over the human sacrifice preparatory to asking his caddy for the niblick. “ Also, if I mistake not, sultana cake and muffins.”

“ Would you require fresh muffins, sir?” asked Blenkinsop.

English Muffins as a Marker of Time

It’s no coincidence that I’ve been noting the publication dates along the way. For me, muffins are closely tied to the literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries — and more broadly, to the English world of that era.

Of course, muffins had been around (and enthusiastically consumed) long before that. But this particular stretch of time feels like their golden age — their cultural zenith. Later in the 20th century, their fame began to fade, and muffins quietly disappeared from many menus altogether.

Agatha Christie’s Time Capsule

Agatha Christie captures this beautifully in At Bertram’s Hotel, written as late as 1965.

The fictional Bertram’s is a kind of time capsule — a sanctuary of old-fashioned Englishness, filled with things you won’t find anywhere else. Miss Marple had stayed there as a young girl in the 1910s, and now, decades later, she marvels at how little has changed.

She relaxed, and abandoning her knitting, let thoughts pass in an idle stream through her head... Selina Hazy... what a pretty cottage she had had in St Mary Mead’s - and now someone had put on that ugly green roof... Muffins... very wasteful in butter... but very good... And fancy serving old-fashioned seed cake! She had never expected, not for a moment, that things would be as much like they used to be...

The hotel’s devotion to tradition is reflected most vividly in its menu. Here, everyone finds some long-forgotten treat to suit their taste. Bess Sedgwick delights in jam doughnuts, Miss Marple opts for seed cake, and Lady Selina Hazy savors her well-buttered muffins.

On this particular day, November the 17th, Lady Selina Hazy, sixty-five, up from Leicestershire, was eating delicious well-buttered muffins with all an elderly lady’s relish. […]

“Only place in London you can still get muffins. Real muffins. Do you know when I went to America last year they had something called muffins on the breakfast menu. Not real muffins at all. Kind of teacake with raisins in them. I mean, why call them muffins?”

Why, Lady Selina, I have the same question looking at my jigsaw puzzle some sixty years later.

It’s telling that everyone who delights in these forgotten pleasures at Bertram’s is of the old school — with the exception of Bess Sedgwick, though she’s not there for the doughnuts after all.

Another fan of old-fashioned, generously buttered muffins is Sir Ronald Graves, known as ‘Father’, an assistant commissioner of Scotland Yard. His fondness for all things solid and unmistakably English is echoed in his choice of tea — a small but telling detail.

Henry smiled benignly. “Yes, sir. Very good indeed our muffins are, if I may say so. Everyone enjoys them. Shall I order you muffins, sir? Indian or China tea?”

“Indian,” said Father. “Or Ceylon if you’ve got it.”

“Certainly we have Ceylon, sir.”

Henry made the faintest gesture with a finger and the pale young man who was his minion departed in search of Ceylon tea and muffins. Henry moved graciously elsewhere. […]

Tea came and the muffins. Father bit deeply. Butter ran down his chin. He wiped it off with a large handkerchief. He drank two cups of tea with plenty of sugar. Then he leaned forward and spoke to the lady sitting in the chair next to him.

I’m not sure many Britons today would follow George Orwell in counting muffins among their national treasures — too much has changed since then.

But there’s no denying it: this is a truly original and delightful creation of English cooks. And no conversation about the traditions of British afternoon tea — especially from a literary or historical perspective — would be complete without a mention of well-buttered muffins.

Still, talking is good — tasting is better.

So let’s move on to the practical part.

Traditional English Muffins: a Recipe

As I’ve mentioned, the dough is essentially the same as for an enriched bread roll. Not all muffins are made equal, of course — older recipes sometimes call for lard instead of butter, and water instead of milk. Generally, the further back you go, the leaner they tend to be. Even today, you’ll find versions without sugar or eggs.

But I remain firmly on the side of the soft, fluffy, buttery kind — and I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

Muffins can vary in both height and diameter. Taller ones may look more impressive, but they take longer to cook through. Larger muffins are often finished in the oven after pan-frying: simply preheat to 170°C and bake for 5 minutes once browned on both sides.

That said, the size in this recipe is perfectly manageable on the stovetop alone — no oven needed. Just a hot pan and a little patience.

Ingredients

(for 10 muffins, approx. 400 g dough)

150 ml milk

2.5 g (¾ tsp) instant dry yeast

250 g plain flour

10 g sugar

½ medium egg (25 g)

15 g unsalted butter

3.5 g (½ tsp) salt

Fine semolina or cornmeal, for dusting

Method

Prepare the yeast mixture

Bring the milk to a lukewarm temperature. Stir in the yeast and leave it to sit for 20–30 minutes.

Prepare other ‘wet’ ingredients

Melt the butter and let it cool slightly.

Bring the egg to room temperature (leave it out of the fridge for an hour, or soak in hot tap water for 10 minutes), beat with a fork, and measure out 25 g.Make the dough

Sift the flour into a large mixing bowl or the bowl of a stand mixer with a dough hook. Stir in the sugar.

Make a well in the centre and pour in the yeast-milk mixture (leaving no yeast sediment behind), melted butter, and egg. Mix until a dough forms, then knead for 5 minutes until smooth.

Add the salt and knead again until thoroughly incorporated. Let the dough rest for a few minutes, then knead 10 minutes more.Let it rise

Cover the bowl with cling film and let the dough rise in a warm place for 1–1½ hours, or until doubled in size.

Shape the muffins

Turn the dough out onto a floured surface. Flatten it to 1.5–2 cm thick — a board pressed on top helps achieve even thickness.

Using a 5–6 cm round cutter, cut out 7 muffins close together. Gather the scraps, divide into 3 equal pieces, and shape them by hand.Dust and proof

Sprinkle semolina on a board or tray. Place the muffins on it and flip each one so both flat surfaces are coated — leave the sides clean.

Cover with a tea towel and let them proof for 30–45 minutes.Cook on the griddle

Heat your griddle or a heavy-bottomed skillet (ideally cast iron) over low heat. A droplet of water should sizzle and vanish instantly — but the pan should not be too hot.

If it’s nonstick, no greasing is needed. Otherwise, rub with a little oil, ghee, or lard.Cook the muffins in batches. Fry for 6–8 minutes per side, until the tops and bottoms are golden brown. The sides should remain pale but become firmer.

Remove to a warm dish (preferably, with a lid). Wipe any loose semolina off the skillet before cooking the next batch.

To serve

Muffins are meant to be eaten warm and generously buttered. Never slice them with a knife — tear them open by hand. Let the butter melt into the crumb and enjoy them while still hot.

They cool quickly, which is why older recipes recommend splitting and buttering them in the kitchen, stacking them high on a warm plate or in a special muffin dish (nestling them close together keeps the heat and helps them soak up all that butter), and serving immediately.

“Where do Bertram’s get hold of their staff? Wonderful! That fellow what’s-his-name — Henry. The one that looks like an archduke or an archbishop, I’m not sure which. Anyway, he serves you tea and muffins — most wonderful muffins! An unforgettable experience.”

“You like muffins with much butter, yes?” Mr Hoffman’s eyes rested for a moment on the rotundity of Father’s figure with disapprobation.

“I expect you can see I do,” said Father.

So — shall we consider this case closed? Or do you have any additional literary sightings to add to this muffin file?

Hope to see you next week. Subscribe if you haven’t yet — and stay tuned for further investigations.